SPECIAL REPORT BY CONSTANTINE KANIKLIDIS, CHIEF OF RESEARCH

A QUICK LOOK AT BREAST CANCER SCREENING: EVIDENCE-BASED GUIDANCE

Many women are hearing and reading confusing and sometimes contradictory things about mammography screening for breast cancer. I am publishing two articles on this controversy which will shortly appear in the Current Oncology journal and which will be posted here before publicattion, but in the meantime here's a quick, plain-English summary of what we know so far:

HOW OFTEN SHOULD I GET A MAMMOGRAM?

All screening-eligible women in the general population should have annual mammograms, NOT biennial (every two years) as currently recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), or by counterparts (like the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC) and various European, Asian and other agencies. The recommendations of these guideline groups - and of many breast cancer advocacy groups - although well-intended, are in error and continue to stand against the best systematically reviewed and critically appraised evidence (as I demonstrate in my forthcoming review), and so rather than helping women, may instead put women at greater risk through failure to detect potential malignancies early so that they can be treated sooner and with less aggressive drugs, thereby improving prognosis. All women starting at latest in their forties (and earlier in certain special and high-risk cases) are therefore advised to commit to regular screening. Remember there is no decisive evidence that age "40" is the magic cutoff; on this see Gina Maisano's Before Forty Initiative here at No Surrender.

MYTH: Mammograms can do more harm (radiation exposure, anxiety, etc.) than good. Although there can be some small risks associated with mammography, a large volume of robust evidence shows that any such potential harm is clearly outweighed by the positives of early disease detection. New technologies I review are beginning to appear like 3D mammography (called tomosynthesis) and ultraFAST MRI, and these will avoid the small potential harms of mammograms, and start to obsolete conventional mammography as the new screening tools going forward.

TIPS

TIP 1: Mammograms do not always have to be so uncomfortable or painful. There are breast cushions, like MammoPad (from Hologic Inc: http://www.mammopad.com), a soft, foam pad that helps minimize discomfort in a screening mammogram, providing a cushion between a woman's breast and the mammography machine. Ask your provider or screening facility about them.

TIP 2: Premenopausal women should consider scheduling their screening for the first week of their menstrual cycle. That's because, as recent evidence has found, breast tissue may be less dense during this week, so a mammogram preformed at this time may be more accurate for some women. Next best time: one week after the start of your period, when the breasts are not as tender at this time so you will not feel as much discomfort or pain when the breasts are pressed between two mammography plates during the X-raying.

FOR WOMEN AT ELEVATED RISK

Women at elevated risk of breast cancer - especially those with a family history of breast cancer or those with a genetic mutation (BRCA) - should discuss effective prevention options and their pros and cons with their oncologist, and should be monitored very closely, generally with regular MRI scans in addition to mammograms.

FOR WOMEN WITH DENSE BREASTS

Women with dense breast - meaning breasts that have a higher proportion of connective (fibrous) and glandular tissue than of fatty tissue - should observe an interleaved scanning protocol, with a yearly mammogram, but interleaved with either (preferably) a breast MRI or a breast ultrasound every six months between mammograms. That's because dense breast tissue cannot be effectively imaged on a regular mammogram, raising the possibility of a malignant lesion embedded in the dense tissue that the mammogram's x-rays cannot reach. In addition since cancer grows primarily in connective tissue in a breast but not typically in fatty tissue, the greater the proportion of connective/non-fatty tissue found in dense breasts puts a women at greater risk of breast cancer. Every women should asks their breast professional (whether their gynecologist or the radiologist) whether their mammogram show that that have dense breasts - and in some states, women must be informed by law - and they should ask what is the degree of density (moderate, high or extreme, etc.), since the more dense a breast is, the greater the potential risk making closer monitoring and preventive measures more critical.

MYTH: That dense breasts are directly related to breast size. Although it is true that dense breasts tend to be more common in younger women and in women with smaller breasts, this is NOT an absolute: any size breasts can be dense, at any age, young or old, although younger women with smaller breasts should be especially vigilant in demanding to know whether they do or do not have dense breasts.

RECOMMENDATIONS ON A CLINICAL BREAST EXAMINATION (CBE)

All women should also have a regular clinical breast examination (CBE) conducted in the office by a skilled health professional (such as a gynecologist). There is some evidence to suggest that there may be some benefit in having the CBE shortly before your mammogram, and make sure that the examiner checks not only the breast but also the lymph areas (underarms and neck region especially).

MONTHLY BREAST SELF-EXAMINATION (BSE)

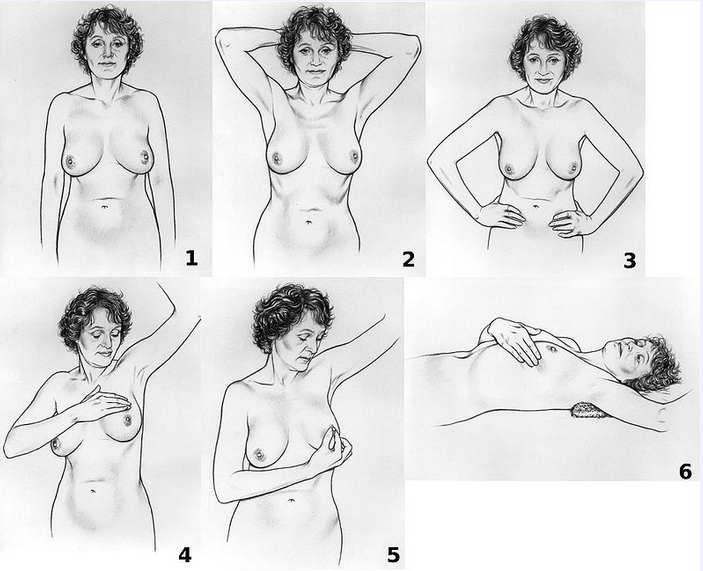

In addition, women of all ages should regularly perform a breast self-examination (BSE), despite recommendations to the contrary from guideline organizations. Although certainly not as effective as mammography screening, nonetheless a breast self-exam when performed properly can be an invaluable ally in detecting potential lesions or lumps early or in between mammograms or clinical breast exams. And the breast awareness that comes from doing regular breast self-exams can be empowering and enable you to detect and be attuned to any abnormalities or changes so they can be checked out by a health professional (remember: most such changes or abnormalities are benign). Unfortunately most women don't perform a breast self-exam regularly, and even those who do often don't know how to conduct an effective one.

Steps 1-3 involve visual inspection of the breasts with the arms in different positions. Step 4 is palpation of the breast. Step 5 is palpation of the nipple. Step 6 is palpation of the breast while lying down.

[Courtesy National Cancer Institute (NCI).]

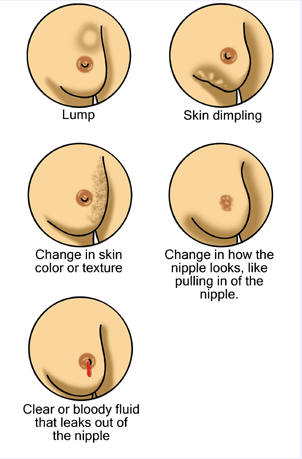

Signs to look for:

[Courtesy Tumore alla mammella, Creative Commons]

There are some excellent videos, one in particular using natural models of different breast sizes, ethnicity, and race, that show the proper way to perform a breast self-examination. Contact this author to obtain (at no charge).

Constantine Kaniklidis

Chief of Research, No Surrender Breast Cancer Foundation

edge@evidencewatch.com

There are some excellent videos, one in particular using natural models of different breast sizes, ethnicity, and race, that show the proper way to perform a breast self-examination. Contact this author to obtain (at no charge).

Constantine Kaniklidis

Chief of Research, No Surrender Breast Cancer Foundation

edge@evidencewatch.com

The No Surrender Breast Cancer Foundation is a 501 c 3 Not-For-Profit Organization. Please see our Disclaimer and Terms of Use.